"One Always Finds One's Burden Again"

A Supporting Paper

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

Of the Department of Art

University of Minnesota

By Jennifer Rogers

In Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements of the Master of Fine Arts

Degree in Art

May 2007

Thesis

The compulsive nature of art making is mimetic of daily chores in the home; it suggests an ongoing struggle with ceaseless labor and the futility of life. In evaluating two distinct 20th Century texts The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Gilman Perkins and The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus the philosophical approach to labor, home, compulsion, and the futility of life will be investigated and discussed in relation to current artistic practices.

I

In 1892 Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, which chronicles a young woman's struggle with neurasthenia, a condition marked by chronic mental and physical fatigue and depression. After being sent to rest in a room with only a nailed down bed, she become obsessed with the never-ending wallpaper pattern that covers the walls.

I lie here in this great immovable bed – it is nailed down, I believe – and follow that pattern about by the hour. It is as good as gymnastics, I assure you. I start, we'll say at the bottom, down in the corner over there where it has not been touched, and I determine for the thousandth time that I will follow that pointless pattern to some sort of an conclusion.[1]

She imagines herself physically trapped inside the wallpaper, between two distinct patterns, tearing it down she frees herself, collapsing further into insanity. Concluding "I've got out at last ... and I've pulled off most of the paper, so you can't put me back!"

For Perkins Gilman the story was in response to her own experience with depression and the 'rest cure' that was common for the day. She was given the advice to "live as domestic a life as possible" and "to have but two hours of intellectual life a day." The paradox, of course, is in the nature of domestic life, which, as Jennifer Fleissner points out in Women, Work, and Compulsion offers anything but rest.

Obsessively counting, cleaning, structuring, their lives according to a painstakingly organized set of repeated habits and routines suggests a deep anxiety about the chaos that seems ever to threaten.[2]

The perpetual tasks of the household environment hardly offer an escape from the anxieties of life, but instead add to the turmoil. The home as a haven of relaxation and rest rather than a place of labor and upkeep denies the realities of home and undermines the work involved in the lifelong commitment to house and family. Like the wallpaper, caring for the home is a never-ending set of repeated tasks.

For the unnamed woman in the story, who is prevented from involvement in any work related task, the endless wallpaper becomes the perfect metaphor for her struggle with anxiety and entrapment. For several weeks she compulsively traces and fights to master the secrets of the wall covering and the end result is not mastery, but more a failure to come to terms with reality.

II

The brilliance of The Yellow Wallpaper is in the pure physicality, timelessness and historical relevance of the text. The extreme denseness and attention to detail reiterates and reinforces the claustrophobic sensibility that is vital to the story. It is necessary that the reader experience's the impenetrable situation that exists for the victim. Fleissner's critique of the naturalist text suggests a continuous, inward looking play with monotony that clearly strengthens the content.

The more (the naturalist text) becomes saturated with descriptions the more it becomes organized & repetitious thus becoming increasingly a closed system that constantly evokes itself.[3]

The exhaustive description is unmistakably imitative of the wallpaper pattern, the act of caring for the home and the sensation of entrapment. The obvious repetition involved in household chores suggests an acute lack of progression. The caretaker is in a constant battle with upkeep that can never be won. The attempt to move forward is always thwarted by the unrelenting dust, dishes, and laundry.

Feminine work has always been ahistorical by the definition of male historians raising children & keeping house has been customarily viewed as timeless routines capable of only minor variations.[4]

It is of course, not only feminine work that can be understood in this manner, but also any labor that involves a recurring set of tasks. This sense of timelessness begins to threaten the larger narrative and flow of history. If one is continually caught up in the details of everyday life, one can never move forward, but instead becomes increasingly stuck. This stuck –ness in turn prevents change from occurring.

III

Albert Camus' Myth of Sisyphus from 1955 is remarkably similar in content to The Yellow Wallpaper but it is in the final conclusion of the two texts that is most significant.

The Gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.[5]

The futility of the actions of both the nameless woman and Sisyphus speak of the inability to escape never-ending labor. The outcome is paramount, for as the nameless woman sinks deeper into madness, Sisyphus finds a way out.

Some would argue that for Sisyphus the struggle is purely physical, but for Camus the struggle goes beyond the corporeal. He argues that because Sisyphus is aware of his fate, he is in a position of acceptance and therefore is imagined happy.

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds ones burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems neither sterile nor futile. Each atom, each stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.[6]

Camus, again takes it one step further to suggest that it is not only Sisyphus' awareness that makes him happy, but also the sense of purpose gained from having a pre-determined task before him for eternity. He is the master of his own fate and therefore no longer has to question his purpose in life.

In Camus' text, unforeseen by the Gods, the punishment of brutal, incessant labor provides a freedom from the absurd and, in doing so, provides meaning. Gilman's unidentified woman is stripped of any purpose and struggles to find a niche for herself between the complex patterns of wallpaper. Her failure to find meaning and purpose for herself, in compulsively tracing the patterns, results in an irrational state of being. In essence both Sisyphus and the unnamed women are punished, but for Camus, it is in the struggle toward self-contemplation, understanding, and finally acceptance that makes happiness possible. Whereas, Gilman's character becomes increasingly stuck in all of the details of the wallpaper, Sisyphus is free.

IV

Essentially the anonymous woman and Sisyphus are caught in a series of repetitive, monotonous, and laborious actions. The inclusion of labor, excessive repetition, compulsion, and aesthetics in art making is similar and in itself an unending process. It is a type of process that can contribute to moments of extreme boredom and fatigue or, like Sisyphus, moments of satisfying self-contemplation.

At the most basic level, labor and hand making put forward the act of doing, the question becomes, what does it mean to be a participant in repetitive labor? For many involved in a continuous act of labor it is a function of survival and a way of life that is motivated by money, history, and obligation, but perhaps more importantly, labor is an indicator of identity and social status. In Work, Consumption and Culture, Paul Ransome states identity and action are intimately linked since the former cannot be expressed without the later.[7] Occupational roles are such strong identifiers that the loss of employment can have severe consequences, "such as loss of self-esteem, loss of personal identity, worry and uncertainty about the future, loss of a sense of purpose, and depression.[8] Therefore labor is an essential part of who we are and in several ways represents a conscious choice on our part of where we fit within the social hierarchy.

Several artists have confronted the issue of labor, repetition, and compulsion in their work. The significance of labor in several of Ann Hamilton's installations echo's American's Puritan heritage while also enacting Sisyphean tasks.[9] In a round (The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada, May 7 – September 6, 1993) Hamilton incorporated the act of knitting. The clinking of the metal needles not only offered a repetitive sound component in an otherwise still, empty warehouse, but also contributed a visual and metaphorical element. More that two miles of white yarn was wrapped around two large columns, forming a skein that the knitter continually worked from. Conceptually and formally each stitch; offer a perpetual accounting of time and space.[10] Every stitch marked the depletion of yarn and the completions of a cylindrical-shaped article that in turn mimic hundreds of stuffed dummies lining the four walls.

Ann Hamilton, a round, 1993

The hand–made canvas dummies, as well as the hollow, empty, and sagging article are not only objects, but remnants of the doer, or in this case the doers. Hand–making does indeed remind us of the makers existence, but as Philip Fisher suggests this idea must be elaborated upon.

Every instance of imagination or making installs the conditions of the body into material separable from the body and detachable from self. Instead of thinking as we traditionally have of a narrow set of objects, mainly art, as the direct record of the making of human image, we need to locate the terms with which we can see every act of making as a making – human, and every act of making as a loss of self – material, a separation and a materialization that invite a second cultural act: the recovery of the self back from materials in which it has been both expressed and buried.[11]

Hamilton has created a world, in which both the act of doing and undoing become a recording of the self. And perhaps this recording can be expanded upon to include not only the individual, but perhaps in a larger sense include all working class people engaged in manual labor. The loss and recovery of self - material that Fisher proposes is a give and take relationship that has the potential to enhance the position of laborer in regards to societies standards.

V

There are two distinct, yet similar, arguments surrounding the relationship between repetition and domestic chore and repetition in art. The repeated act of labor is significant in either case. For some it suggests a stuck-ness or lack of creativity, but for others it represents a means of self-reflection.

The rituals of housekeeping, which at one time were considered "woman's work", are little more than a series of mindless tasks, with little altercation that Gilman suggests would drive women to a morbid state of monomania or obsessively overdeveloped will.[12] The lack of change in daily regiment is worsened by the realities of housekeeping, in that it is a never-ending process that cannot be conquered.

Stagnation and complacency for an artist are equally problematic. The best example of this can be found in the work of Medardo Rosso, an Eighteenth Century Italian sculptor and contemporary of Auguste Rodin. Rosso spent the last twenty years of his life stuck. Instead of creating new models he recast the old. Art historians have attributed this to his obsession with the process of sculptural reproduction and many have hypothesized on the reasons behind his decision to halt the creative process.[13] Rosso's fascination with reproduction has led some to speculate that a lack of creativity was to blame. For Jungian Theorist, Patricia Berry, repetition is a part of everyday behavior that becomes apparent in the stories we repeatedly tell and the phrases we cannot stop saying. She goes on to pose the following questions, Have we some deep investment in our repetitions – some love for them? Is there beauty there? Berry concludes that: We repeat what we find to be self–reflectively beautiful. What we love, what we long for, tells us something about ourselves.[14] So, what does this mean for Rosso?

As he made and remade his objects, his self was willfully constituted, let go, and then reconstituted by his objects in an open-ended, dialectical relationship.[15]

Can this complex give and take relationship between the artist and object be applied to homemaker and home? In New England Nun Mary Wilkins Freeman's offers up an alternative to Gilman's perspective on the drudgery of housework when she describes her main character, Louisa 's approach to chores as being that of an artist.

Louisa had almost the enthusiasm of an artist over the mere order and cleanliness of her solitary home. She had throbs of genuine triumph at the sight of the windowpanes which she polished until it shone like jewels.[16]

The idea that homemaking is an aesthetic process that can be understood as a self-reflective practice, is an interesting proposition and suggests that housework can be described as art through the lack of usefulness, mere pleasure and aesthetic worth. The idea that housework can be seen as a pleasurable, creative act not only recalls a freedom and acceptance, but could also be understood as a contemplative act.[17]

Yet, as we see with the artist Yayoi Kusama, the act of repetition can be taken several steps further into a world of compulsion. In a conversation with Akira Tatehata, Tatehara suggests that Kusama's "obsession with repetition signals both desire, and the need to escape." How can repetition represent self-reflection, beauty, desire, and a need to escape? The idea of being confined or trapped in ones mind, which obsessive self-examination would suggest, recalls the woman from The Yellow Wallpaper and proposes an internal struggle that speaks strongly of longing and the need for autonomy.

The struggle with compulsion in Kusama's work is most clearly evident in the polka dot pieces titled Infinity Nets from the late fifties and early sixties, which plainly illustrate the manic studio practice that epitomized her career. The highlight is the 10 meter white Infinity Net painting exhibited at the Stephen Radich Gallery in New York in 1961. The overall effect is of frantic replication that denies any sense of an organization or pattern. The quiet pallet of pale blues, pinks, whites and ecru mute the overall appearance. This is not a bold statement created from a fear or a need to escape, but rather speaks of a need to dive even deeper inside oneself.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net, 1961

Kusama's fifty-year struggle with obsessional neurosis becomes apparent in this painting. The end result is not the anger and frustration one would expect from illness but rather the approach is a cathartic experience of acceptance, patience, focus and surprising clarity.

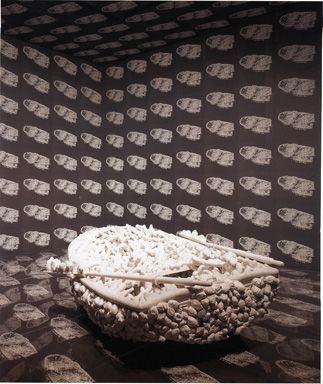

Interestingly Kusama's desire is not for perfection, but rather there is an insistent imperfection in all of (her) work.[18] The handmade-ness of her work reinserts a sense of humanness that runs counter to much of the repetitive work of the time, such as the work being produced by the Warhol Factory. The imperfection argues against anonymous, industrial seriality and champion's process over art, experience over consumption.[19] Kusama's One Thousand Boats show, which took place at the Gertrude Stein Gallery in New York City, is a prime example of her interest in experience and her brilliance in bringing attention to the solitary object in relation to the multiple.

The installation consisted of an eight-foot rowboat and nine hundred and ninety nine photographs of the boat. The photographs lined the floors and walls of the small, dimly lit hallway and room where the boat was on display. The viewer experienced the boat, from three distinct perspectives simultaneously, the first being from both two and three dimensions, and the second from multiple images to singular object, and third from a representation of the boat to the real boat.

Yayoi Kusama, Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show, 1963

The result was dramatic and highlighted the value of the original object over the reproducible counterparts. In doing so, she boldly argued against the massed produced industrial object, instead favoring the process and labor inherent to the handmade.

VI

My thesis exhibition consists of four works. The first, Whiteroom is an eight-foot by four-foot by six-foot room. The exterior two by fours and drywall expose the building process. The interior with a slightly slanted floor has walls lined with wallpaper, painted white and redesigned using linocut prints and graphite. The pattern is a repeating pile of plates, bowls, cups, and bottles. The room is empty except for a single bare bulb in the ceiling. The second piece, Yellowroom, is a large, white seven-foot by seven-foot by six-foot u-shaped room built from simple white shelving. The shelving is stacked with approximately two thousand ceramic plates, bowls, cups, and bottles. The objects are glazed a soft yellow that has the appearance of food or fossil. The third is Blind, a twenty four-foot by four-foot piece of satin quilting material. The cream fabric is covered with the pencil tracings of the linocuts and occasional stitching with white embroidery thread. The fabric hangs on the wall, draping onto the floor where it is folded in a neat, clean stack. The fourth, Wallpaper, is a group of forty-four identical lithographs that repeat, covering the wall. The cream paper softens the strong black in that fills the space. The actively drawn imagery is again of the plates, bowls, cups, and bottles.

Inspired by The Yellow Wallpaper, Whiteroom confronts one's struggle with the endless labor and the senselessness of life. The wallpaper that lines the walls consists of a recurring pattern of household objects that represent home, labor, and compulsion.

Jennifer Rogers, Whiteroom, 2007

The confined space is overcome with repetition and process that reiterate the never-ending routine of daily toil. The sameness also speaks of a loss of reality, time, place and an inability to move forward eliciting a sense of entrapment. The whiteness brings about a feeling of frozenness and incompleteness that is marked through the intentional emptiness.

Yellowroom by contrast is full of piles and stacks of the three-dimensional counterparts that paper the walls of Whiteroom. The experience becomes at once more tangible and real. The space is equally inundated with home, labor and repetition, yet the viewer is allowed the physical and visual freedom that suggests a recognition and acceptance of time, labor, space and futility. The warmth of the yellow objects, that surround the viewer, brings a sense of time and continued vitality.

Jennifer Rogers, Yellowroom, 2007

The interplay between the two pieces is both formal and conceptual. The relationship between the two and three-dimensions directly confronts the varied meaning behind different modes of representation. The suggestion of the imagined sensations of weight, depth and denseness in contrast to these genuine attributes places the work in a location of contemplation that reinforce the ideas of self-reflection, beauty, and desire.

The history, tradition, and use of functional ceramics in everyday life is referenced in the press molded plates, cups, and bowls. The importance of the handmade object supports the argument for the human need for purpose and the freedom of choice. The ability to create reasserts the human desire for choice, as Yayoi Kusama boldly stated anything mass-produced robs us of our freedom.[20]

In summary, the metaphor of home and labor allow for an in depth look at several of the complex issues of human existence, such as, purpose, perception, and choice. As illustrated through The Yellow Wallpaper and The Myth of Sisyphus, continual repetition can provide sensations of entrapment or provide purpose to life. At the most basic level, work displaces the notion of futility instead replacing it with utility, which in essence gives meaning to life.

[1] Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The Yellow Wallpaper. (The Norton Introduction to Literature, Eight Edition,1892) 678

[2] Jennifer L. Fleissner. Women, Compulsion, and Modernity. (University of Chicago Press, 2004) 42

[3] Jennifer L. Fleissner. Women, Compulsion, and Modernity. (University of Chicago Press, 2004) 47

[4] Ann Douglas. The Feminization of American Culture. (Alfred A Knopf, 1977) 184

[5] Albert Camus. The Myth of Sisyphus. (First Vintage National Edition, 1991) 119

[6] Albert Camus. The Myth of Sisyphus. (First Vintage National Edition, 1991) 123

[7] Paul Ransome. Work, Consumption, and Culture. (Sage Publications, 2005) 90

[8] T. Keefe. The Stress of Unemployment. (Social Work 1984) 29, (3): 264- 68

[9] Joan Simon. Ann Hamilton. (Harry N. Adams, 2002) 44

[10] Joan Simon. Ann Hamilton. (Harry N. Adams, 2002) 45

[11] Philip Fisher. Making and Effacing Art: Modern Art in a Culture of Museums. (Cambridge, Mass, and London, Harvard University Press, 1991) 233

[12] Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper. (Small and Maynard Boston, MA, 1899) 233

[13] Sharon Hecker. Medardo Rosso: Second Impressions. (Yale University Press: London and New Haven, 2003) 54

[14] Patricia Berry. Echo's Subtle Body. (Spring Publications, Dallas, Texas) 118, 119

[15] Sharon Hecker. Medardo Rosso: Second Impressions. (Yale University Press: London and New Haven, 2003) 57

[16] Mary Wilkins Freeman. The New England Nun. (Ridgewood, New Jersey, Gregg Press, 1967) 112

[17] Marjorie Pryse. Sex, Class, and Category: Crisis Reading Jewett's Transitivity. (American Literature, 1998) 517 - 49

[18] Laura Hoptman. Yayoi Kusama: A Reckoning. (Phaidon Press, 2000) 44

[19] Laura Hoptman. Yayoi Kusama: A Reckoning. (Phaidon Press, 2000) 59

[20] Laura Hoptman. Yayoi Kusama: A Reckoning. (Phaidon Press, 2000) 56

Bibliography

Berry, Patricia. Echo's Subtle Body. Spring Publications, Dallas, Texas. 1982

Camus, Albert. Myth of Sisyphus. First Vintage International Edition, UK. 1991

Douglas, Ann. The Feminization of American Culture. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, New York. 1977

Fisher, Philip. Making and Effacing Art: Modern Art in a Culture of Museums. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, UK. 1991

Fleissner, Jennifer L. Women, Compulsion, and Modernity. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. 2004

Freeman, Mary Wilkins. The New England Nun. Gregg Press, Ridgewood, New Jersey. 1967

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. The Yellow Wallpaper. The Norton Introduction to Literature, Eighth Edition, W. W Norton and Company, New York, New York. 1892

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper. Small and Maynard, Boston, MA, 1899. <www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/history/lavender/wallpaper.html> (accessed October 2006)

Hecker, Sharon, Harry Cooper. Medardo Rosso: Second Impressions. Yale University Press, London, UK and New Haven, Connecticut>. 2003

Hopman, Laura, Akira Tatehata, and Udo Kultermann. Yayoi Kusama.Phaidon Press, London, UK. 2000

Keefe, T. The Stress of Unemployment, Social Work 29 (1984) (3): 264- 68.

Miller, Daniel. Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Berg Publishers, Oxford. 2001

Pryse, Margorie. Sex,Class, and, Category: Crisis Reading Jewett's Transitivity. American Literature. 70:3, Duke University Press.1998 (517- 49)

Ransome, Paul. Work, Consumption, & Culture. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California. 2005

Simon, Joan. Ann Hamilton. Harry N. Abrams Inc, New York, New York. 2002